Silent Compliance and Manufactured Belief: What Soviet Society Teaches Us About Ourselves Today. Modelling It All.

A personal reflection on life under Soviet propaganda and its disturbing parallels in modern democratic societies, and data science framework to study the phenomenon. Six types of citizens to model.

This article continues the analysis I began in my previous piece, exploring the growing parallels between Soviet-era ideological control and what we increasingly observe in Canada today. It unfolds in two parts: first, a reflection on historical patterns based on my personal experience living in the Soviet Union; and second, a data-driven model that uses those parallels to assess where we are now—and where we may be heading.

Part I: Six Archetypes in a Controlled Society — A Soviet-Era Typology

Growing up in the Soviet Union, I lived under a constant stream of propaganda. It wasn't just on TV—it saturated everything. Every classroom, every workplace, every newspaper and radio station. Songs, films, novels, and science lectures were steeped in political loyalty to the Communist Party. There was no such thing as neutral ground.

Today, living in Canada, I begin to notice some of the same patterns: the encouragement to report colleagues, the suppression of dissenting opinions, and the growing atmosphere of fear in speaking freely. To help explain the anatomy of such a system, I’d like to share a framework based on my personal experience and those of millions who lived through Soviet life. This framework includes six types of citizens who emerged under intense ideological control.

Group 1: The Naïve (Ideologically Programmed)

These were the people who genuinely believed what they were told. They trusted the newspapers and radio completely. They couldn’t imagine their government lying to them. Many were schoolchildren, like Pavlik Morozov, the boy glorified by the regime for reporting his own father to the authorities. In Soviet mythology, he became a model citizen—a symbol of loyalty to the state above family.

As children, we were taught to admire him. Students were subtly encouraged to report on their classmates and even teachers who questioned the party line. This created a chilling climate of mutual suspicion. The state didn’t need surveillance cameras—it had hearts and minds.

Reference: Soviet textbooks, children's books, and youth organizations like the Pioneers glorified Pavlik Morozov to indoctrinate children into state loyalty.

See: “Pavlik Morozov and Soviet Mythmaking,” Yale Review of Books, 2001

Group 2: The Conformists (Fearful)

This group doesn’t believe in the message but complies out of fear. In the USSR, professionals routinely denounced others to keep their positions. One striking example was the public condemnation of Boris Pasternak, author of Doctor Zhivago, when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1958. Nearly all major Soviet writers’ unions and media outlets condemned him. Many did so unwillingly, under pressure. They knew he had done nothing wrong—but they signed statements and wrote condemnations anyway. It was about survival.

Reference:

Medvedev, Zhores. Ten Years After. Penguin, 1973.

Nobel Prize & Pasternak

Group 3: The Dissenters

These were the rare individuals who dared to speak out. Andrei Sakharov, the brilliant physicist and dissident, became the voice of conscience in a system built on obedience. For his criticism of the government, he was exiled and isolated, but his courage exposed the moral bankruptcy of the regime.

Others like Solzhenitsyn, Medvedev, and countless lesser-known heroes endured surveillance, job loss, imprisonment, and worse. But they preserved their dignity—and history has vindicated them.

Reference:

Sakharov, Andrei. Memoirs. Vintage Books, 1992.

Hoover Institution: “The KGB and Western Plots Against the Soviet Union”

Group 4: The Silent Professionals

Then there was a fourth group—those who made a conscious effort to stay out of politics altogether.

My father was one of them: a passionate physicist devoted to his work on semiconductors, who steered clear of ideological debates whenever possible. Like many doctors, teachers, engineers, and artists of his time, he deliberately avoided management roles that might force him to betray colleagues or enforce party lines. Instead, he focused on what truly mattered to him—his family, his research, and the enduring joys of music, sports, art, and close friendships.

His quiet resistance was not through protest, but through a steadfast commitment to human values—truth, beauty, curiosity, and kindness. He sought refuge not in ideology but in science, music, nature, and the joy of learning. In a world saturated with propaganda, his way of living—rooted in integrity, wonder, and quiet compassion—was itself a form of spiritual defiance.

These individuals formed the moral backbone of Soviet society. They weren’t naive, nor driven by fear. Instead, they focused on living with integrity—caring for their families, leading by example, and striving to be the best professionals and human beings they could be. In a climate of control and conformity, their quiet dedication to truth, kindness, and personal excellence was a form of everyday courage.

Group 5: The Enforcers – KGB and Informants

Then there was a fifth group—the active enforcers of the system. These included official KGB agents as well as civilian informants. Their task was to surveil everyone else, collect information, and report deviations.

Some did it out of ideology. Others for favors or career advancement. Many were planted in universities, laboratories, workplaces—even among neighbors. These enforcers ensured the system remained in place not by overt violence, but by quiet intimidation. Their presence was invisible but deeply felt.

Reference:

KGB Lexicon: The Soviet Intelligence Officer’s Handbook (Routledge, 1993)

Mitrokhin Archive, Cambridge University

Group 5: The Indifferent Majority (Mob Mentality)

Finally, there was and will always be the largest group - those who don’t care much either way. They follow whatever seems normal, rarely question authority, and often serve as the passive enablers of authoritarian systems. In both Nazi Germany and the USSR, this group allowed atrocities to unfold by simply “going along.”

Reference:

Hannah Arendt’s concept of “the banality of evil” in Eichmann in Jerusalem;

Also: Yuri Bezmenov's interviews, where he identifies the critical role of uninformed and passive citizens in maintaining ideological systems.

Parallels to Canada Today

The same five types of citizen responses can be observed—albeit in different forms—in modern Canada:

1. Naïve Citizens: These are the well-meaning individuals who believe everything they hear from legacy media or government bulletins. They genuinely think they are defending democracy when reporting a coworker’s "offensive" comment. Like Pavlik Morozov, they are shaped by institutions to place ideological loyalty above personal relationships.

2. Conformists Who Know Better: These are professionals who sign disciplinary letters, HR memos, or diversity statements not because they believe in them, but because they fear losing their jobs. They watch colleagues suffer unfair treatment and stay silent—or worse, participate—just to protect their careers.

3. Dissenters: These are rare but critical voices—academics, whistleblowers, doctors, union members—who speak out publicly about flawed policies, censorship, or political bias. Often labeled as dangerous, they are disinvited from conferences, suspended, or pushed out of the workplace.

4. Silent Professionals: Many Canadians fall into this group. They quietly go about their work, trying to avoid institutional politics. But in an environment where silence may be interpreted as agreement or complicity, even neutrality becomes precarious.

5. Enforcers: In the Canadian context, these are HR and Labor Relations staff, diversity officers, compliance managers, and certain media figures who enforce ideological norms. They may not wear uniforms, but their function mirrors that of the First Department in Soviet times: to monitor, report, and penalize ideological deviation.

Why This Framework Matters

Understanding these five roles helps us see that the system of ideological enforcement is not sustained only from the top down. It’s maintained laterally and from within—through social dynamics, fear, and belief.

If we do not want to repeat the trajectory of censorship, repression, and moral compromise that defined the Soviet Union, we must:

Encourage free inquiry and open debate

Reject fear-based conformity

Question the role of institutional enforcers

Defend the right to disagree

History is not just a warning—it is a pattern. And if we are not honest about where we stand within that pattern, we risk becoming part of it.

As one of former PIPSC (Public Service Professionals Union) executives posted on Facebook:

“It didn’t start with gas chambers. It started with one party controlling the media… deciding what is truth… when good people turned a blend eye and let it happen”.

This is also why write my articles on this (IVIM) and my other (DG4VP) substack, as as further explained in my Open Letter to an Informant, written in response to someone who objected to seeing my articles shared on LinkedIn.

Part II: Modeling Populations in Propaganda-Driven Societies. From Memory to Modeling: A Data Scientist’s View.

As a data scientist, I couldn’t resist the urge to quantify what I lived through, and to apply my data science instincts to a question like this: how do population segments distribute themselves under systems of ideological pressure or propaganda? Whether we’re looking at the Soviet Union in the 1970s or Canada in the 2020s, there are discernible group types that emerge.

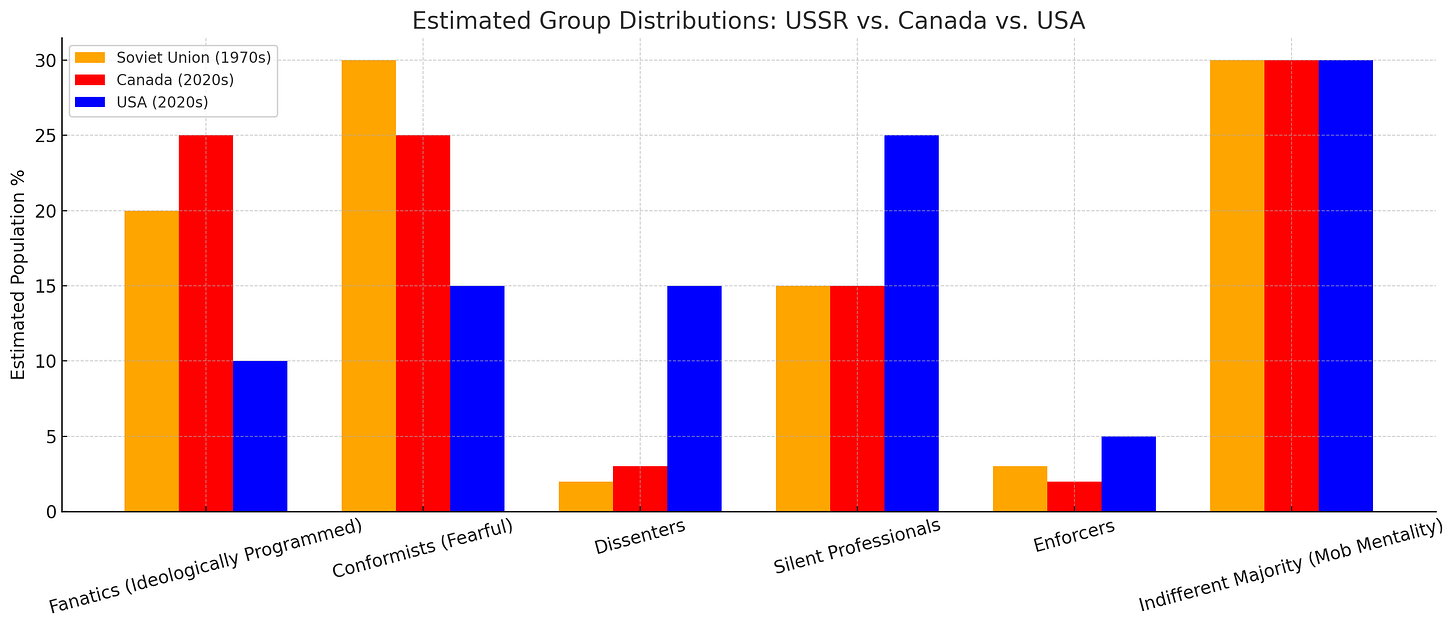

Using approximate estimates based on Soviet history, Canadian trends, and cultural observation, I created a model to visualize these societal types.

Here is the bar chart comparing the estimated percentage of the population in each of the five main groups between the Soviet Union (circa 1970s) and modern-day Canada (2020s).

These estimates are based on my own sociopolitical observations. They illustrate how similar roles might persist in different forms across regimes.

Of course, these estimates are not precise. But even a rough model can be informative. It shows a worrying convergence—Canada may be moving closer to a system of enforced ideological conformity.

What makes this especially useful is the possibility of tracking change over time. If we revisit this chart next year, we may see whether Canada is drifting further toward—or away from—the Soviet-style structure of managed beliefs and punished dissent.

This isn’t just a model of the past. It’s a lens on the present—and a forecast for the future.

Using this approach, we can also compare key societal dynamics—such as the spread of propaganda, the depth of fear-based conformity, and the strength of democratic resistance—from one country to another.

To dive deeper, let’s illustrate this with a few more charts.

Chart 1: USSR vs. Canada (2020s)

This chart shows how Canada today resembles a softer echo of the USSR, with fewer dissenters and a greater presence of both ideological zeal and fearful conformity.

Chart 2: Canada Then and Now

In the early 2000s, Canada had more open dissent and less cultural pressure. The rise in “fanatics” and “conformists” over two decades is a shift worth serious attention.

Chart 3: USSR vs. Canada vs. USA

This visualization highlights how the U.S. maintains a larger share of dissenters and silent professionals, with lower levels of naïve conformity and ideological enforcers—suggesting greater resilience to centralized propaganda, especially when compared to both the USSR and Canada (as seen in the previous chart).

Comparing all three, it becomes clear that the U.S. still maintains a higher tolerance for dissent and ideological diversity, whereas Canada appears to be shifting in the direction of Soviet-style compliance culture.

Why This Matters Now

Some may argue that today’s context is different—no gulags, no forced exile. But control doesn’t need to be violent to be real. All it needs is silence. When people fear speaking out, when professionals lose their jobs for questioning government narratives, when students are encouraged to report on peers, the mechanism is already in place.

It starts in schools. It spreads through workplaces. And it ends—if unchecked—in a society where truth itself becomes a liability.

What Can Be Done?

Recognize these patterns. Label them. Teach them.

Create space for open debate—not just in courts or parliaments, but in break rooms and classrooms.

Protect dissenters, not silence them.

Reduce the power of internal enforcement bureaucracies that now act as ideological gatekeepers.

Most of all: educate the indifferent. Because when they awaken, societies begin to heal.

Disclaimer

This article's opinions are that of the author, not of any institution. It is not for legal or medical advice.

Acknowledgment

This article is written based on my personal experience growing up in the USSR, with assistance from ChatGPT for editing and structuring.

Support This Work Across All Channels

If you believe in open dialogue, informed choice, and exploring underreported perspectives, help keep the conversation going—like and share this article on your preferred platform.

You can follow me here:

🔹 LinkedIn

🔹 Facebook

🔹 Twitter/X

🔹 YouTube (@Dr.Dmitry.Gorodnichy), YouTube (@IVIM)

My articles are, and will always remain, free to read.

This is great analysis, Dmitry. It's something that many of us can see happening in Canada. I must admit that I was blind to this until the last five years.

This is why I believe that it is important to have immigrants such as yourself who have a needed skill plus a life experience from your own country that can help others. Our immigration system is broken.